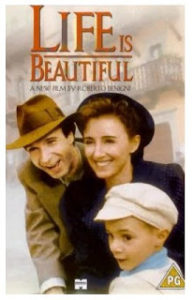

In the 1997 Italian film, Life is Beautiful, director and actor, Roberto Benigni, illustrates life during the Holocaust in a concentration camp in Germany. The protagonist, Guido, is a Jewish Italian man who falls in love with a local school teacher, Dora, and together have a son called Giosue. Years later, Guido and Giosue, along with other Jewish residents are forcefully packed in a train to be sent to a concentration camp. Although, Dora is not Jewish, she still joins them to be closer to her husband and child. In an effort to shield Giosue from the horrors of the camp and to protect his innocence, Guido convinces his son that they are in a game in which the ultimate prize is a tank. Rules include hiding from the officers, staying quiet, and no crying or complaining of hunger. Gudio is successful with this till the end when American soldiers come to the camp and rescue all survivors. The film exhibits the Holocaust with humor in an attempt to convey that there is beauty in every dark situation. Is living in fear with limited resources what makes life beautiful?

The idea of life being beautiful can be taken in various ways depending on perspective. Benigni’s aim in the film is to convey that, “even under the most desperate circumstances, life can be not only meaningful but even profoundly beautiful” (Gunderman 3). He does this by adding humor into the scenes, “convinced that laughter can save us” (Viano 29). However, how can life be beautiful under an oppressed dictator, fearing your last meal? Therefore, Benigni’s attempt in the film to illustrate the Holocaust as a child’s game in order to emphasize the idea that “life is beautiful” once you see past the negative, improperly portrays this distressing event; ultimately, depicting Jewish identity and life during these times in a faulty manner.

Despite the various alarming concerns afflicted with the film, several critics agree with Benigni choice to use humor in the film. According to Abraham Foxman, American lawyer and activist, “[it] is so poignant, it is so sensitive, it is so informed by creative genius, that the answer is – I give it a wholehearted endorsement” (Kotzin 45). Foxman applauds the film for its production as it wonderfully exhibits the scenes with vivid details, which is why the film itself won three Academy Awards. Maurizio Viano, professor at Wellesley College, further supports this claim by arguing that, “ Fog makes the vision difficult and a voiceover reminds us that the film we’re about to see is a fairytale (and therefore demands suspension of the rules of realism)” (Viano 32). In other words, Viano explains that the film is not meant to be seen in a realistically but rather in an imaginative manner like we see with fairytales. However, how can we not abide by the rules of realism when discussing a sensitive subject such as the Holocaust? Certainly the Holocaust was no fairytale and thus deserves to be portrayed rightly in order to bring awareness to the injustice that occurred during this time. American film critic, Gerald Peary, argues that Benigni has a “revisionist upbeat Holocaust view” (Peary), indicating his lost perception in regards to the event as he depicts the Holocaust with adverse humor. The lack of truth given towards the Holocaust not only directs some to a false awareness of the subject, but also, inaccurately depicts the occurrences during these times by making light of grave situations.

Humor is employed greatly through many scenes with many sensitive comments. In the concentration camp, every “prisoner” was given a tattoo of a number that would identify them, depriving them of their true identity already. However, when Guido shows this mark to his son, he says it’s proof to show that they have signed up for the game as if he was lucky to get it and be admitted to the camp. However, this is not humor but an insensitive remark to the survivors who live with this tattoo as a scar of an unforgettable memory of their misery in the camp. Furthermore, when Giosue tells his father that he heard people are being burned in ovens, Guido jokingly dismisses it and says “that’ll be the day” (01:23:51), disregarding the fact that “nearly 2,700,000 Jews” (“Killing Centers: In Depth”) died in this manner. Therefore, this denotes offensive humor, especially to those who lost loved ones as a result of this cruelty or were forced to “exterminate” their own peers and bury them. This continues to depict the lack of truth behind the scenes as we don’t see “the brutality, the starvation, the beatings, the humiliations” (Niv 17) associated with the Holocaust.

Peary continues to support the idea of “Holocaust misrepresentations” in the film, by revealing how Benigni only focuses on the living as he did by showing the survival of “many, many from his camp (too many!)”. Writer Kobi Niv even states, “the concentration camp. . .was too good, too nice, too amusing a place, too devoid of death” (Niv 16) because the film fails to portray the multiple deaths associated with the Holocaust. For example, at the end, when the American soldiers come to the rescue, we see a swarm of people exiting the camp indicating that the same amount who entered the camp returned to freedom as well. When in reality, approximately six million were killed by Nazis and only sixty-six thousands survived to tell their stories (“The Holocaust Explained”). In addition, Peary notes how the end is illustrated with “sunshine, green fields, and flowers, and instantly reunited families” as if the Holocaust ended with a happily ever after. The film even displays the reuniting of Giosue and Dora in a pool of joy and laughter without any signs of grief for or acknowledgement of Guido’s death, after being killed by a Nazi. Therefore, this portrayal, lacks to show the sorrow and depression instilled within many after the event, such as PTSD, or the fact that many weren’t able to reunite with their families after several months or even years of searching.

The idea of treating the camp as a game raises many concerns especially to those touched closely by the subject. As Peary sarcastically says, “the hiding out and forced starvation are actually kind of … fun” (Peary). Guido and his family must have spent months at the camp, yet he successfully convinced Giosue that he was in a game this long; an impossible task in reality. During the holocaust, no one was safe, especially children. “As many as 1.5 million children, about 1 million of them Jewish, were killed by Nazi Germany and its collaborators” (“Children during the Holocaust”). Not counting those who died from starvation or exposure, rarely any child was safe and if not many, all, at one point had encounters with the horrors of the camp.

The comedy in the film misleads its fanatics and general audience with the historical details dealing with the Holocaust and only adds mockery to this unfortunate event. In today’s society, various forms of media are intensely broadcasted throughout the world. As generations pass, we become more inclined to believe everything we see behind a screen. From this, the truth behind every story and news can be misinterpreted. As a result, spreading fallacious reports on a subject. Media’s influences now greatly focus on entertainment rather than veracity, due to public demand. This is particularly shown through the film which, ironically enough, “won the Best Jewish Experience Award at the Jerusalem Film Festival” (Peary). Even so, the inaccurate representation of historic events serve as offensive media to those who experienced the horrors of a concentration camp at first hand and who identify with the subject one way or another.

Presenting traumatic periods like the Holocaust to the general public can be problematic for any director, especially if not experienced at first hand. Therefore, establishing truth behind the imaginative scenes in accordance to the reality can be sensitive to manipulate as it can offend or be easily misinterpreted by many. However, bringing humor into a appalling event like this, trivializes the subject, ultimately, causing it to lose meaning and significance. As a result, the film, Life is Beautiful, doesn’t truly delineate the horrors behind the Holocaust and misguides its audience into believing that this period in time was in fact, not dreadful due to the comedy incorporated through some of the grave scenes. Life under dictatorship, while laboring for the enemy, hoping your life would be spared, must have been grueling and horrifying; certainly it was “no laughing matter” (Peary).

Works Cited

Benigni, Roberto, director. Life Is Beautiful. Miramax Home Entertainment, 1999.

Gunderman, R. B. (2015). Life is Beautiful. Academic Radiology, 22(3), 408-409.

doi:10.1016/j.acra.2014.11.002

Niv, K. (2003). Life is beautiful, but not for Jews: Another view of the film by Benigni. Landham,

MD: Scarecrow Press.

Peary, Gerald. “No Laughing Matter?” Weekly Wire, 2 Nov. 1998.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/children-during-the-holocaust. Accessed 27Nov. 2018

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/killing-centers-in-depth. Accessed 16 Dec.2018

Viano, Maurizio. “‘Life Is Beautiful’: Reception, Allegory, and Holocaust Laughter.” Film

Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 1999, pp. 26–34., doi:10.2307/3697210.

“What Happened to the Survivors?” Deportation and Transportation – The Holocaust Explained:

Designed for Schools,

www.theholocaustexplained.org/survival-and-legacy/liberation-the-survivors/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2018.